This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Pottery

Pottery presents one of the most important and ancient crafts recorded in the mankind history through archaeological finds which characterize the culture of each period. Pottery collection of the Museum of Byzantine Culture comprises hundreds of intact vessels and thousands of shards, which are dated from the Hellenistic period and up to the 20th century. As a whole they are found in excavations in Thessaloniki and its region. Most of these clay vessels were unearthed in the fill of public and private building of a city-palimpsest, with many phases of reuse, like Thessaloniki. Only the vessels which were found in sealed burial groups can offer some clear and secure data.

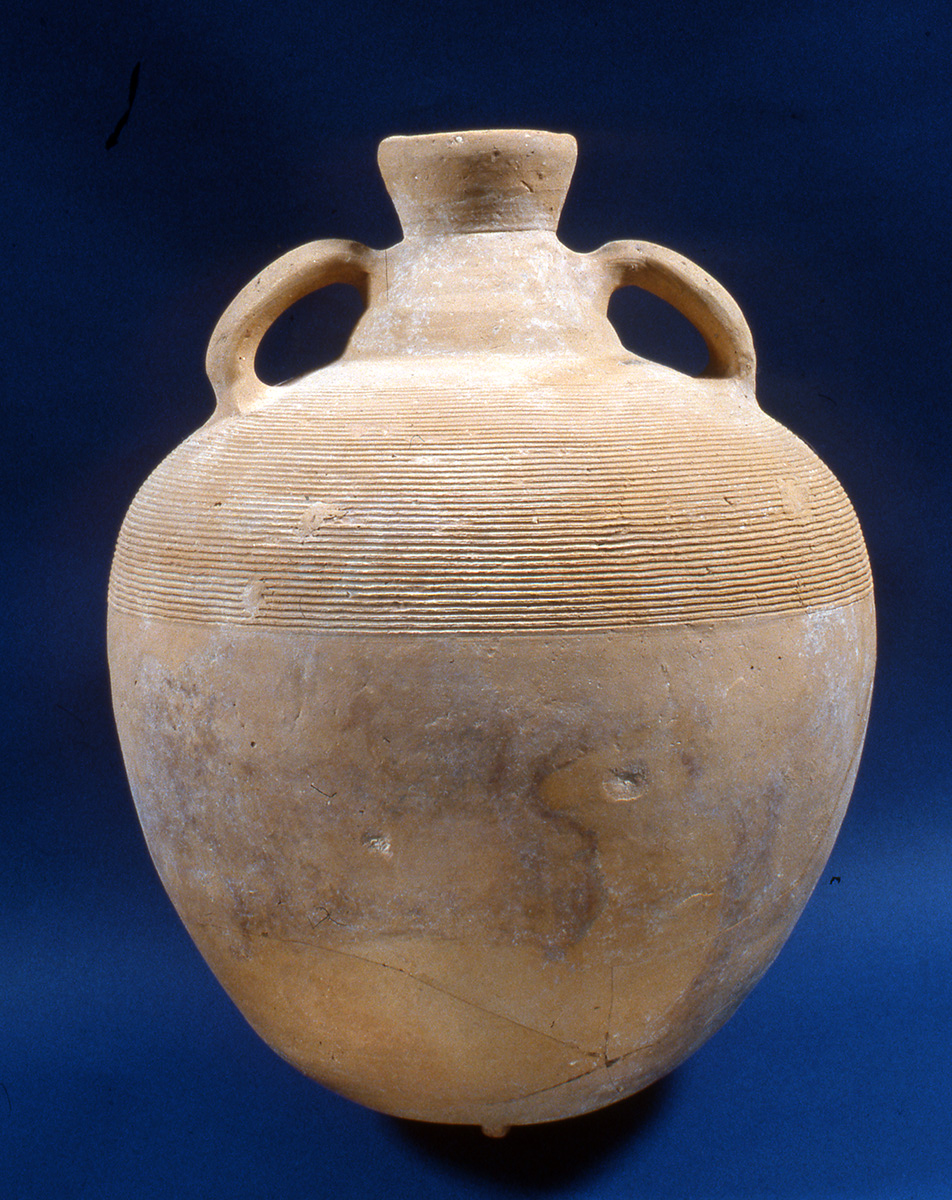

Clay vessels of the Early Christian period, meant for transportation and preservation of goods, and tableware, as well as burial finds, present common forms for all Mediterranean states of the Roman Empire, although we do not know their production sites. These vessels some times are impressive in their simplicity, or due to their rich decoration and sometimes for the ways that they have been reused.

During the Middle Byzantine period (9th-12th c.) the technique of glazing re-appears and evolves significantly. A thin layer of glaze usually covers the interior of the vessel primarily aiming to the waterproofing of the clay, which is one of the biggest problems that potters faced diachronically.

However, the bright and rich colors that were produced by the use of metal oxides they also resulted to a more aesthetic appearance of the vessels. The pottery of this period is not adequately represented in Thessaloniki. A few shards of pottery (polychrome and early glazed ones), products of Constantinople’s famous workshops, probably are reflecting the commercial relations between the two cities.

Of particular interest for the Middle Byzantine Thessaloniki are the 1200 amphorae (intact or fragmentary) discovered as a filler of the domes of the Church of St. Sophia. Although they represent popular forms known throughout the Byzantine Empire, there are however several indications that connect them to local workshops.

Byzantine workshops from the early 13th century, because of the mass production of glazed vessels, adopted the practice to fire glazed pottery in columns with tripodisks between the vessels, preventing them so from sticking together. The decoration techniques include painting, engraving, the relief and the champlevé. In this period, known as Palaiologan era, workshops operating in Thessaloniki produce high quality vessels, competing worthily those of Constantinople and from the city’s harbor they are exported to countries in West and East.

The first years of Ottoman rule the pottery workshops continue to produce large quantities of pottery. From the 17th century onwards the workshops are ‘transferred’ in cities like Kütahya and Iznik, which maintained the Byzantine tradition of production as it was formed in Thessaloniki, changing only the decorative motives which were allowed by the new religion.

A significant number of porcelain vessels dated between the 18th and early 20th century, coming from Northern Europe, makes clear the importance of the city’s harbor and the transportation of various goods throughout the Ottoman Empire.